A bond is an agreement between you and a 2nd party to lend them money in return for interest payments and the return of your capital at the end of the agreement¹.

However, there is a major misconception about investing in bonds. Most people think of a bond as lending money where they will hold the bond until it matures and collect interest payments.

The other group looks at a bond as purchasing the debt of some entity. Bonds have a market price and can be bought with the intention of selling it for a higher price; Just like a stock, real estate, crypto etc.

The surprising thing about bonds is that many of them that have done better than stocks on a risk adjusted basis since 1980.

Summary

- A bond is an agreement for you to lend money in return for interest payments and the return of your capital at the end of the agreement.

- The main aspects of bonds that you should know before investing are:

- The issuer of the bond

- Length of Maturity

- Coupon rate

- Credit Rating

- Callability

- All the other risks inherent to a financial investment

- Although the coupon rate is the primary focus of many investors, bonds have prices just like stocks. They can be bought and sold for a profit between issuance and maturity.

- Due to their low correlation to stocks and decent returns, bonds can improve portfolio diversification.

- Your risk tolerance will determine what % of your portfolio you hold in bonds.

How bonds work

In the world of bonds there are two interest rates that you should be aware of: The market interest rate and the coupon rate on an individual bond.

Market Interest Rate

The market interest rate is the foundation for the rates of all bonds that fall into a specific segment (Type of debt, length of maturity and credit rating).

For example, 30 year government bonds serve as the starting point or foundation for all 30 year bonds because they’re considered the least risky. The coupon rates of all other bonds are derived by taking this base interest rate and adjusting it up and down based on the various qualities of that individual bond.

If you’re looking at a corporate bond then you will add a little bit on top of the base rate. If you’re looking at a lower credit quality corporate bond, you’d add even more on top of the base rate.

Coupon Interest Rate

When a bond is first issued it has a a coupon rate and maturity date specified. The coupon rate is the interest rate that a single bond will pay the holder until maturity. It is determined by taking the base rate and adjusting it up and down based on the risk profile of the individual bond.

The coupon rate can be fixed for the life of the bond or, if you choose a variable/floating rate bond , the coupon will change as the market interest rate changes.

Bond market law of relativity

You often hear that if the market interest rate increases then the price of a bond decreases and vice versa. This is only half true. It only holds for fixed coupon bonds or bonds whose coupon rate does not change.

However, it does not hold for variable rate bonds.

Rather than the absolute level of the two rates, It is the relative level or “spread” between the two that creates the law we are all so familiar with

Market rate vs coupon spread increases, price of single bond decreases

Market rate vs coupon spread decreases, price of single bond increases

Once again, the key here is the spread between the two rates, not the absolute levels. If the coupon is fixed then any change in the market rate will change the spread between the two rates. This will cause the price of the bond to change according to the law stated above.

However, if the coupon is variable then the market interest rate could go up 100% and have no affect on the price of the bond, as long as the coupon also goes up by 100%.

What causes relative changes in the interest rate vs coupon you ask?

The answer is changes in market conditions and the underlying risks of the the bond. Just like anything else of value, If market conditions or risks get more favorable, then the spread will decrease and the price will rise. But if conditions and risks get worse, the spread will increase and the price will drop.

Fuzzy or unfamiliar with the risks of financial assets? you should go back and quickly review our risk/return framework.

Pros

- You know all the terms before investing

- Predictable income streams and returns

- Capital preservation

- Diversification

- Debt holders get paid before stock owners

There is a pecking order2 here though. Secured debt has first dibs, then unsecured debt and then owners/stockholders of the company get the scraps if there are any.

- Some bonds receive federal and/or state tax advantages (Municipal and US treasuries)

- Lower volatility than many alternatives

Cons

- See list of risks that apply to all bonds – inflation, interest rate risk and call risk are amplified

- Credit rating agencies have been proven to be liars in the past

Leading up to the Great financial Crisis, credit rating agencies3 were receiving tons of fees in exchange for lenient ratings. Investors, thinking they could trust a AAA rating, were wiped out because the AAA rating was a bunch of baloney.

Credit ratings of a single bond are fairly straightforward and verifiable. You have access to the company’s financial and legal statements and you can verify whether the rating provided by a credit agency is close to how you perceive the risk. However, when you start investing in bond mutual funds or ETFs, and especially packaged/combined debt securities, the risk that you’re investing in questionably rated debts increases.

- Returns are generally lower than most other assets

Considerations when investing in bonds

Out of the last 41 years, the 10-year Treasury has returned positive real returns in 37 of those years. The average return over this period is +9%. Because of the long track record of consistently positive returns & the added diversification, anyone with money invested should consider having a portion of their portfolio in bonds.

There are several questions you must answer when deciding what percentage of your net worth to invest in bonds:

What is your risk tolerance?

Risk tolerance is how well you are able to handle fluctuations in the value of your investments. Primarily losses.

In general, the more risk you are willing to live with, the higher the potential return of your portfolio. Notice I said potential. Just because you take more risk doesn’t mean you automatically generate higher returns. You could just end up loosing more than you otherwise would have.

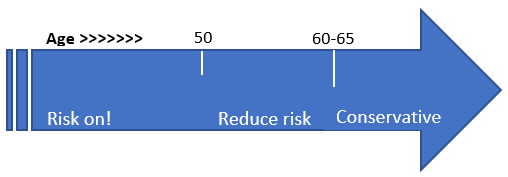

As time goes on you’ll get closer and closer to needing to use the money (and you’re getting older!) so the additional risk is not worth the incremental increase in your assets. You’ll tend to drift towards less risky investments.

To gauge your risk tolerance you should answer the following

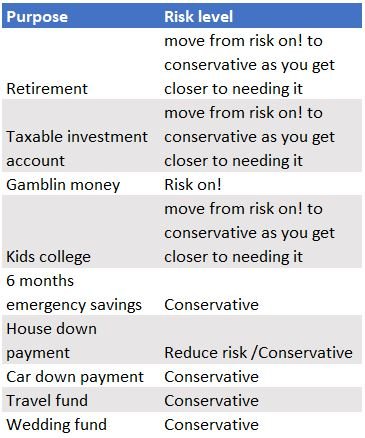

Money that is needed in the next 2-3 years should probably be held in more conservative investments such as high yield savings accounts or money market mutual funds/ETF’s.

Down payments on a car or house, savings for children’s college that will be used in the next year or two, savings for your upcoming wedding, a travel fund etc., are all instances where you’d want to be more conservative with that money.

Your ability to be conservative with the money is highly dependent on the inflation rate.

If inflation is not a problem and you can maintain your purchasing power by keeping the money in ultra-safe investments, then it’s usually the best to do so.

On the other hand, if the prices of the items that you intend to spend the money on are increasing faster than the interest rate you’re receiving in conservative investments, then you almost have to consider keeping at least a portion invested to try to maintain your purchasing power.

The percentage is up to you but in most circumstances it’s probably smartest to keep at least 40-50% in safe investments unless inflation is super high, like 10% or more.

If you are young and don’t need the money for a long time (retirement money), then mathematically speaking, you can afford to have a fairly large portion of your portfolio allocated to riskier investments offering higher returns.

If you receive poor returns for a few years (even 5 years), you’ll have plenty of time to recover.

The older you are, or the closer you get to needing the money, the generally accepted wisdom is to reduce risk. It’s wise to allocate a smaller portion to riskier assets and to increase your allocation to safer assets like cash, money market funds and/or bonds.

Are you a person who can ignore market fluctuations and hold on for the long term?

If so, there is nothing wrong with taking on risk in pursuit of higher returns. As always, make sure you understand the risks and have a backup plan incase it backfires and ends up costing you money that you should have been protecting.

A useful exercise is to ask yourself, If I lost 40% of this money:

- Would it severely affect my daily financial situation?

- Would it cause undue stress and negatively affect my health or happiness?

- Would it jeopardize the goal for which I’m investing?

If you answer yes, to any of these questions it’s probably too much risk for you.

Ask yourself the same questions if you lost 25% of the money, and again if you lost 15% of the money and so on.

Generally, you have to be willing to take a 30% loss to invest in the stock market. Most of the time you will make money, especially over long periods of 10 years or more, but big losses do come around once every 10-15 years.

Bond market segmentation

Within the bond market there are several ways to categorize the different types of debt you can invest in. The most common being the issuer of the debt (Govt, Corporate, Mortgage etc.), the credit rating of the issuer, the number of years until maturity and the location of the issuer.

International bonds are out of the scope of this article but can play an important role in a portfolio. Please talk to a certified financial advisor before making any investment decisions you are not comfortable making on your own.

There are corporations known as credit rating agencies that do analysis on a ton of the debt being issued and they assign a grade (AKA credit rating) to the issuances they cover.

These grades group the issuers based on their default risk, nothing more. They are an opinion supported by historical data4 regarding the ability and willingness of the issuer to meet their financial obligations.

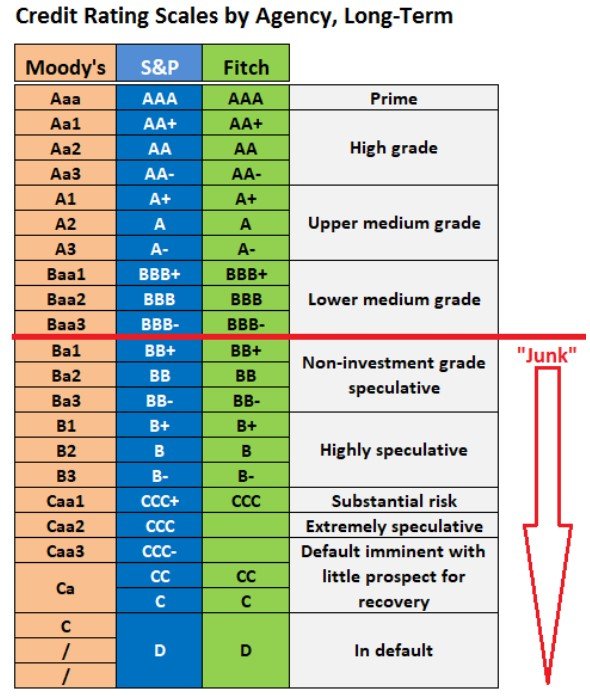

The three main agencies are Moody’s, Standard & Poor’s and Fitch. Each one has their own scale that ranges from AAA (highest grade possible – lowest probability of default), down to C (imminent default) or D (active default).

The interest rate you will receive moves inversely to the credit rating of that particular issuance.

The higher the rating (i.e. the lower the risk of default), the lower the interest rate and vice versa. You can get some really high interest rates in the “junk bond” territory but you will also face significantly higher default risk.

There are a couple more features of credit ratings as it relates to the risk and return of debt:

- The lower the credit rating, the more sensitive a bond will be to market forces & vice versa.

- In general, the lower the credit rating, the less liquidity there is in the market for that security. The less interest there will be in the security and the harder it will be to find a buyer if you want to sell. This is not always the case so make sure you check the daily volume and the bid/ask spreads before investing.

Lastly, I feel it’s important to understand that credit rating agencies are for profit corporations. They have the incentive to provide the issuer of debt with the highest possible rating, within reason. And if the economy falters, they downgrade the debt that you invested in and you watch the value plummet.

If you don’t believe me, please read this article from council of foreign relations which states an unfathomable fact: “In 2007, as housing prices began to tumble, Moody’s downgraded 83 percent (!!!) of the $869 billion in mortgage securities it had rated at the AAA level in 2006.”5

You should never fully trust the credit rating of a bond that you’re interested in. Please learn to understand the 3 main financial statements so that you can determine for yourself how financially sound the issuer is. You can then use the credit rating, and the information that comes with it, as additional information in your thoroughly researched investment decision.

I’m not saying that the credit ratings are crap. In fact, they’re quite accurate. The problem arises when something negative happens and you suddenly learn that a thing you thought the issuer could handle (based on the credit rating) is now pushing them to the brink of default and you’re screwed.

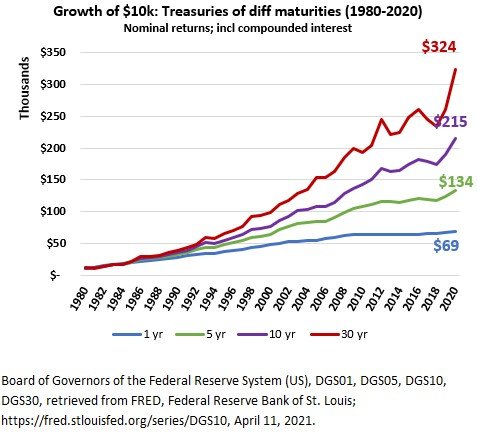

Another aspect that should factor into your investment decision when it comes to debt is the length of maturity.

You can find pretty darn close to any length you want. There are some that are only a month, 3 months or 6 months while others can range from 1 year up to 30 years. Some governments have even issued 100-year bonds!

The longer the maturity, the more sensitive the price is to changes in interest rates.

Take two bonds, one with a maturity of 1 year and the other at 30 years. Assuming all other qualities of two bonds are the same, the price of the 30 year bond will increase by a larger percentage if interest rates decrease. On the flip side, if interest rates go up, the 30-year bond will decrease in value by a larger percentage. This is called Duration.

One strategy used to manage the risk associated with varying lengths of maturities is called bond laddering.

There are dozens of types of debt that you can invest in. In this section, we are going to focus on government, municipal and corporate debt as these are the most common. I will cover asset backed bonds such as mortgage bonds in a later post.

You can purchase individual bonds, mutual funds or ETFs through any of the main brokerages (Schwab, TD Ameritrade, Merrill Lynch etc.). With mutual funds and ETF’s, not only do you let the professionals do the security selecting for you, you get the benefit of added diversification (possibly) because you will be investing in many bonds, not just one.

Government

This is debt issued by any sovereign government. The proceeds are used to finance any type of government spending ranging from the country’s infrastructure to financing the military, rolling over existing debt, and even paying the salaries of government workers.

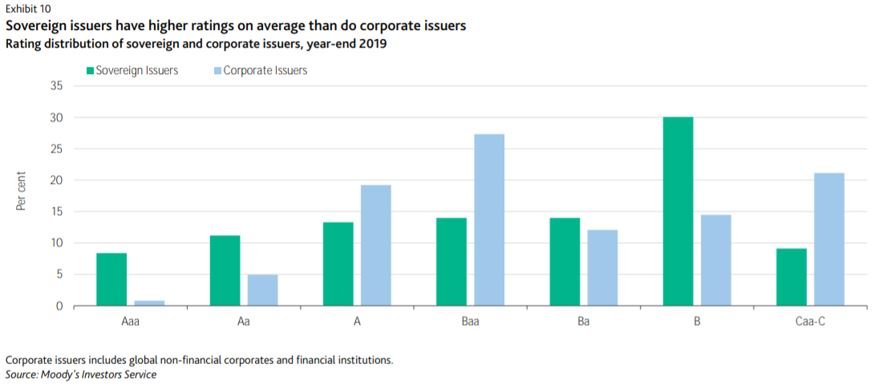

Although most developed countries have an investment grade credit rating, a country’s rating can range anywhere from investment grade down to highly speculative and imminent default.

A large percentage of these speculative grade countries are located in the African, Middle Eastern or Latin American regions.

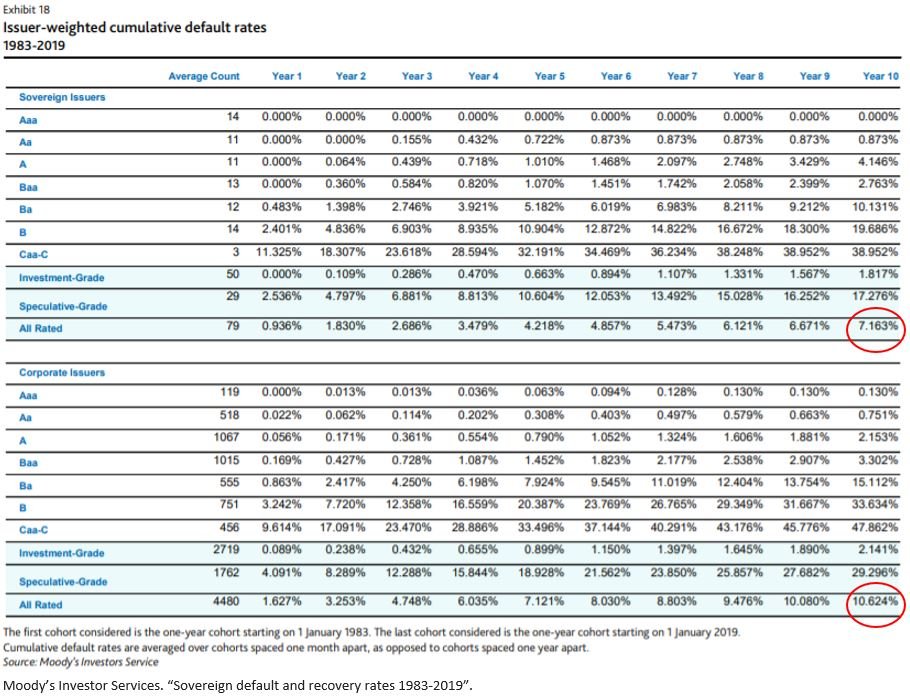

Even then, research by Moody’s shows that a larger percentage of governments are rated investment grade than corporations are.

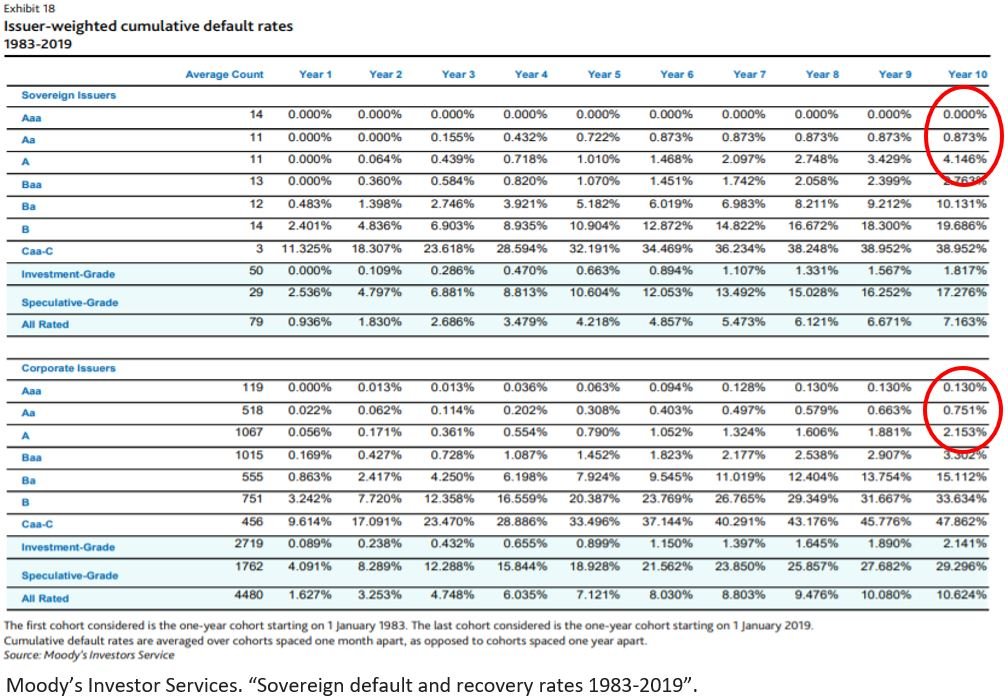

The same research shows that from 1983-2019, governments averaged a 7.16% default rate over each 10 year period,6 while corporations averaged 10.62%.

Because of lower default rates, government debt is considered less risky than all other types of comparable debt.

In addition to the low default rates, many markets for government debt are huge and extremely active. This high liquidity also reduces your risk as an investor because if you want to sell your security it’s very easy to find a buyer.

The result is lower returns/interest rates on government debt than other types of debt.

Corporate

Corporations issue debt primarily to finance buildings, machinery or research and development, or to buy another company, buy back their own stock or refinance their existing debt.

Corporate bonds tend to have higher interest rates than comparable government debt because a corporation can’t print its own currency and give it to you to satisfy their debts. In other words, they’re riskier.

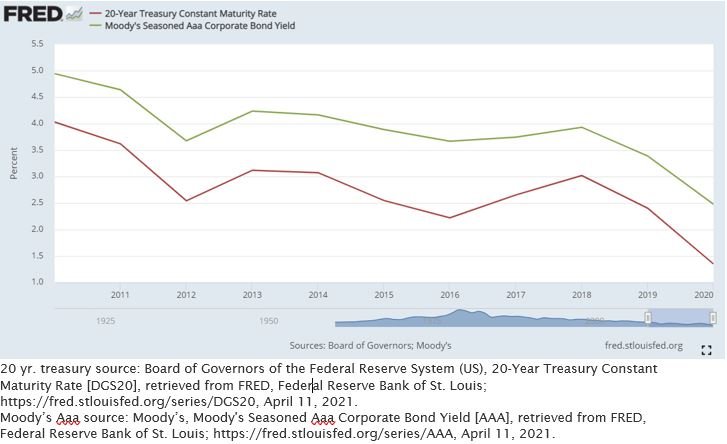

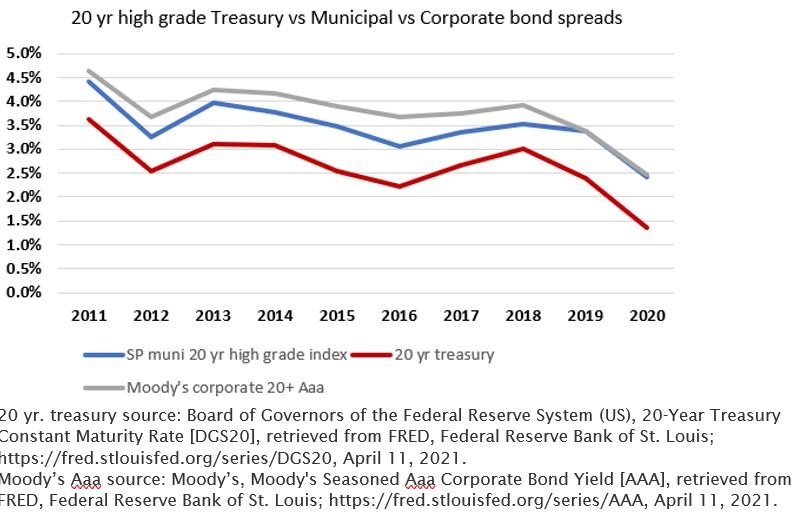

As you can see in the chart below, the spread between government and corporate yields for a 20-year security ranged from 0.75% to 1.5% over the past 10 years.8

One thing that surprised me about the Moody’s default rate chart we reviewed earlier was that for high grade debt (Aaa-A), corporate default rates were actually lower than the comparable government default rates over each 10-year period.

This is one reason investors dig high grade corporate bonds. You can get low default rates plus an extra 1% interest! And if you purchase high grade debt of well know companies, you will get the benefit of a highly liquid market as well.

Municipal Bonds

Municipal bonds (AKA munis) are issued by state and local governments, or their agencies (i.e. utilities, nonprofits etc.), to fund their budgets and projects.

There are a lot of varying opinions about munis because they’re more complicated due to the addition of the tax variable. Also, would you be surprised to know that there are taxable munis?

Yes, the product that is thought to be tax free, is available as a taxable security or, even if you choose the tax-free kind, can end up being taxable or not as good a tax benefit as you think.

On the other hand, the competitive post-tax returns and safety put munis in the conversation with all other bonds.

Pros

- The interest can be exempt from federal tax and, in most cases, state tax as well.

Because of the tax advantages, munis make the most sense for people who are high earners or live in a high tax state. Millionaires in California love em! You don’t get any benefit if you live in a state without an income tax, like Texas.

- Munis offer a slightly higher interest rate than treasuries and just about the same as corporates. The spread between treasuries and US munis average about 0.8% over the past 10 years.8

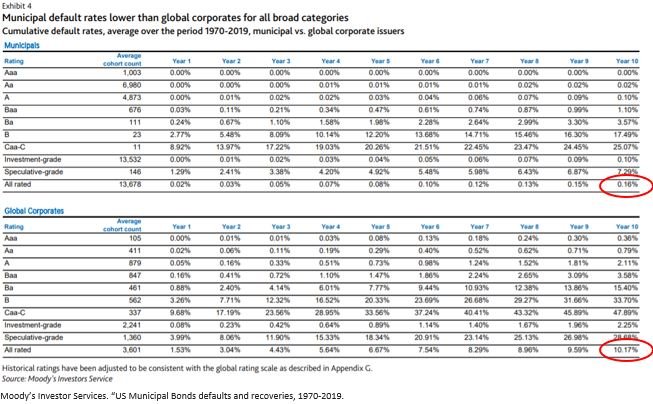

- In addition to their higher returns than government debt, US municipal default rates are extremely low (0.16%).9

- Fairly liquid markets

Provided you choose one that has a lotta daily trading volume. You should also pay attention to the bid/ask spread of any muni you invest in. If the spread is too large, it could cause a problem if you need to quickly sell your security

Cons

- Your tax situation can complicate the profitability of your investment

Be aware that there are many tax snares out there that can change the profitability of this type of debt. I recommend reading this article from Investopedia regarding severalpossible tax snares of muni bonds. And, as always, do thorough research into each investment before investing.

- Many munis are callable

This is when the issuer of the bond has the option to pay off the bond early thereby reducing the amount of interest you were expecting to receive. It’s also very likely to reduce the interest rate you will receive on your next investment (the only time it makes sense to pay a bond off early is if interest rates have dropped).

Not only are you no longer receiving any interest payments until you can reinvest the money, but now you’re going to be investing at lower interest rates (or you’ll have to find a different investment).

Corporate bonds can be callable too so just make sure you know what you’re investing in.

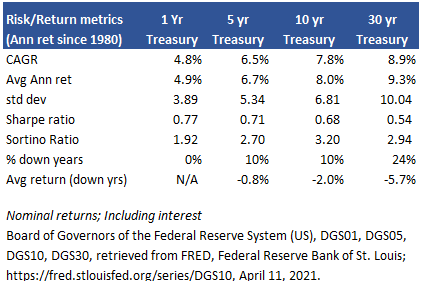

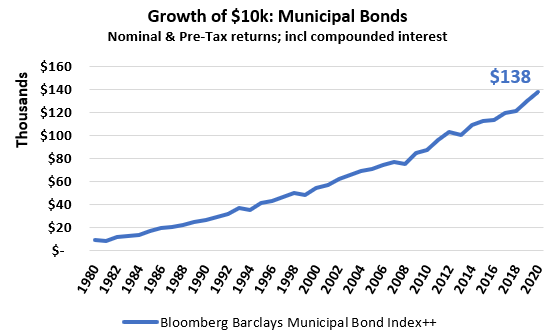

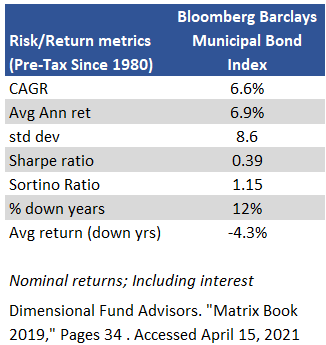

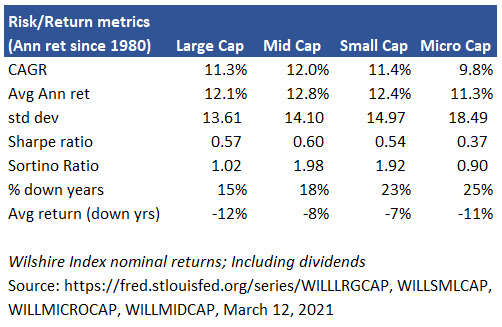

Historical risk & return metrics of bonds

So far, we’ve looked primarily at the variables that affect the risks and returns of bonds. Now let’s look at the actual returns over different maturities and compare them to US stocks to see if any of them stick out.

While US stocks have handily outperformed US Treasuries in absolute terms, the significantly lower volatility puts bonds ahead of stocks when taking return volatility (AKA “risk”) into account.

Three things stick out when looking at the metrics below.

- The 7-9% nominal returns on government bonds ain’t that bad

- Bonds have lost money about 1/2 as frequently as stocks

- When bonds do lose money, their loss is about 1/2 as much as stocks

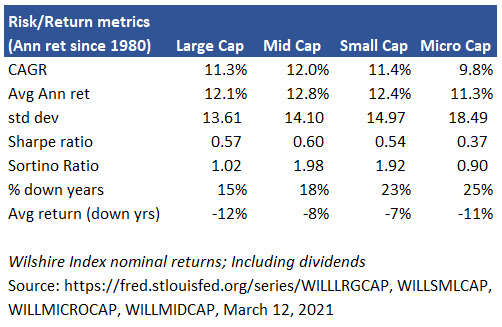

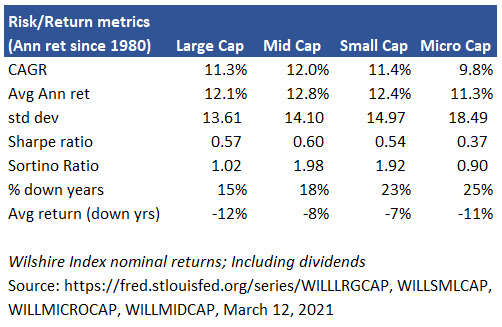

Here are historical US stock returns for comparison

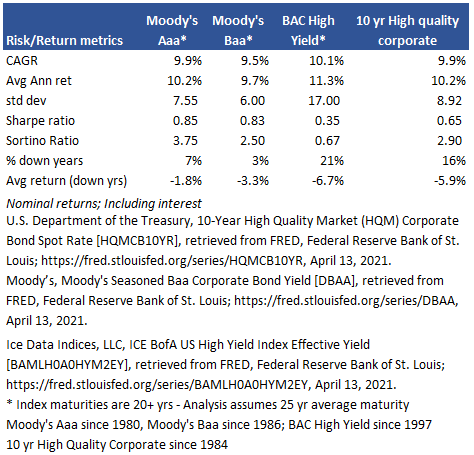

10% per year is good, especially given the limited price volatility. Of course, this assumes that none of the companies default. For investment grade bonds, this is not an unreasonable assumption. The chances of default in investment grade corporate bonds are quite low (approx. 2.5% according to the Moody’s default data covered above).

The true value is seen when looking at the risk adjusted returns, % down years and avg loss during down years.

So far, we see that municipal bonds offer higher yields than treasuries but lower default rates than corporates. They also have tax advantages in many cases as well.

What about the total returns?

At 6.6% compounded per year, the returns are decent but not great. But don’t forget that this doesn’t factor in the potential tax advantages. I leave it this way so that these returns are comparable to the pre-tax treasury and corporate returns shown earlier.

If we just do a high-level application of the Tax Equivalent Yield, you’ll see that the muni return is quite similar to corporates and higher than treasuries.

Tax Equivalent Yield

In order to compare returns between pre-tax and post-tax bonds you need to either convert the post-tax to a pre-tax basis or convert the pre-tax to a post-tax basis. To do this you have to calculate the Tax Equivalent Yield.

This is the rate that a non-tax advantaged bond would have to pay to equal the return on the tax advantaged bond.

Muni interest rate = Corporate interest rate * (1 – tax rate+)

Or the way I like to apply it

Corporate interest rate = Muni interest rate / (1 – tax rate+)

Ex) Muni % rate = 4%; Your Federal + state tax rate = 32% Required Corp bond int rate = 4%/(1-32%) = 5.88%

In order for the corporate bond to have the same post tax return as the muni yielding 4%, it would have to have a pre-tax interest rate of at least 5.88%.

Using the 2nd formula, you could just check to see if there are any comparable corporate bonds (i.e. Same or similar maturity, credit rating etc.) that yield more than the tax equivalent yield.

But you’d be doing yourself a disservice!

A couple things to keep in mind when applying the Tax Equivalent Yield:

- This method ignores variables other than the tax benefit

As I demonstrated earlier, munis have much lower default rates than comparable corporates. So why would you be willing to accept the same post-tax rate on a corporate as you’re getting for a muni?

You shouldn’t! You should be looking for a corporate bond that pays more on a post-tax basis than what you’d get from a muni.

- Make sure that your muni is tax free in your state. There are many munis out there that are not state tax free.

- Treasuries are also federal income tax free so make sure you equalize the post-tax interest rates on treasuries as well.

Going back to our return comparison between US bonds and US stocks. Why invest in bonds and accept a lower return than stocks just to reduce return volatility? Most people just want to get the highest return possible.

- You could just be a conservative investor – i.e. Your risk tolerance is not that high

- You’re getting close to needing the money. When you are getting close to having to use the money you’ve saved, a decrease in the value of your investments hurts you much more than an increase would help you.

As a matter of fact, a drop in the value of your savings in the first few years of retirement can literally derail your whole retirement. This is referred to as sequence of returns risk7.

This is why preservation of your initial investment is so important at certain times. Stocks take a back seat to treasuries when it comes to capital preservation.

- Federal and municipal bonds have tax advantages not considered in these calculations so the realized returns are slightly higher on an after-tax basis

- Returns are more predictable – This makes planning more accurate

- Diversification – The primary purpose of diversification is to reduce the overall volatility of a portfolio and limit losses while not compromising too much on return.

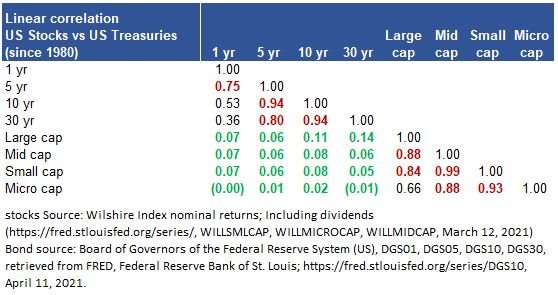

Do bonds offer diversification?

Think of diversification as decentralizing your investments. it’s the strategy of putting a portion of your financial wealth in different investments whos returns are lightly correlated, uncorrelated or even negatively correlated to your other investments. This way, you theoretically protect your whole nest egg from taking a nasty hit.

The low correlation between US stocks and treasuries is obvious. Lack of correlation plus a decent return are the primary objectives of diversification.

I was curious to see how treasuries performed in the years that stocks fell. Large cap stocks have fallen in 6 years since 1980 and in every one of those years, bonds had positive returns with a 9.2% average return. Even more evidence that bonds do their job as diversifiers in a portfolio with stocks.

There are three main reasons for this:

- Stocks almost always fall during recessions with investors looking for safer assets. They flock to treasuries which are generally accepted as super safe.

- Interest rates naturally fall during recessions and as explained above, when interest rates fall, bond prices rise.

- Bonds can be held to maturity so even if prices decline, your loss or reduction in return is only on paper. You don’t recognize a loss unless you sell it. So, if you hold your bonds and collect the interest payment, your return will be positive no matter what happens to interest rates or stocks or any other assets class for that matter.

So, we now mathematically know that the returns of US stocks and US treasuries are uncorrelated. But does this help an all stock portfolio?

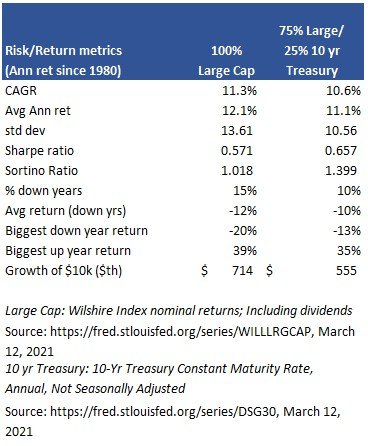

To answer this question let’s compare the risk/return metrics of an all Large Cap portfolio to a 75% large cap & 25% 10 yr. US treasury portfolio.

This pretty much aligns with what I was saying earlier. It’s not a guarantee that your losses will decrease or that your returns will increase, but it’s possible. And what you see here is that the returns actually went down.

However, the volatility and loss metrics of the portfolio improved:

- Volatility (Std dev) decreased by 22%

- Risk adjusted returns improved significantly

- The # of down years dropped from 6 to 4

- The largest loss dropped by 7% (from -20% to -13%) while the largest increase dropped only 4% (from 39% to 35%)

Many people see that you would have ended up with $160k more dollars sticking with 100% large caps. All they care about is the amount of money I have at the end of the investment. They would take the 100% large cap portfolio.

If the returns were guaranteed to turn out even close to the last 40 years then of course, I would too.

But past performance is not a guarantee of future performance. We don’t know what will happen over the next 40 years. Some would argue that it’s smarter to take the portfolio with the lower volatility, lower probability of losing money and higher risk adjusted returns.

Whatever you choose is up to you. You will reap the rewards and suffer the consequences of your choices.

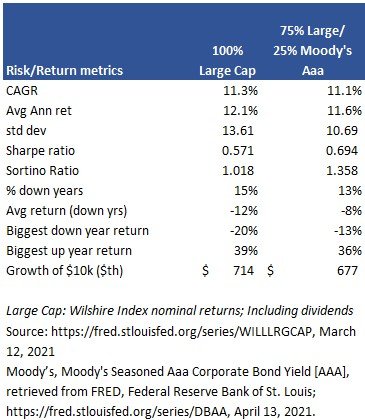

Just like treasuries, corporate bonds also offer what it takes to diversify your portfolio; Low correlation and good returns.

What do the metrics look like with 75% US stocks and 25% Aaa corporate bonds?

Now we’re to the point where the ending portfolio value is negligibly lower than 100% Large cap portfolio. We get lower price volatility and less downside risk along with it and we didn’t sacrifice much on the upside (36% highest return is only 3% lower than 100% Large cap).

I think I’ve made the case that high-quality corporate bonds belong in your portfolio. Maybe not much, depending on all the main factors (age, risk tolerance, targeted return, goals for the money, time till retirement etc.), but something.

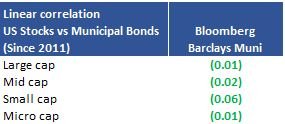

As far as diversification goes, munis are great. While treasuries and corporates offered low correlations, municipal bonds offer inverse correlation to stocks. In other words, when stocks fall, muni’s tend to go up on average and vise versa.

I wouldn’t say that they are better diversifiers than treasuries or corporates though. The correlations of treasuries and corporates are low enough that having a negative correlation does not necessarily improve a portfolio’s return or return volatility.

If we just do a high-level application of the Tax Equivalent Yield, you’ll see that muni returns are quite similar to corporates.

Add extremely low historical default rates into the mix and you can make a case that munis are just as good an investment as corporates or treasuries.

So whether you’re investing in bonds because of their diversification qualities, their predictable cash flows or super low default rates (as is the case for US treasuries and muni bonds), you should always keep in mind that they’re tradable securities like any stock, bond, mutual fund, ETF etc.

Going into the investment with the plan of collecting interest payments until maturity is fine, but make sure you pay attention to the price of your security so you can capitalize on any large price increases.

If you do end up selling prior to maturity, make sure you know where you’re going to reinvest the money and estimate a total return over a 10-year period to make sure that your decision is sound.

Lastly, please understand that at this moment, we are at historically low bond yields due primarily to the massive debt load that

the US government, corporations and consumers have amassed over the past 40 years. The affect of this debt load is to keep yields low. Therefore, we could continue the trend of declining interest rates and rising bond prices, but there will come a time, (when is anybody’s guess) when interest rates across the board will start to rise. As they do, the prices of most, if not all, bonds will drop. If you’re holding bonds at that time, you will have to make a choice between holding your bonds until maturity to collect the interest payments while avoiding a capital loss, or selling so you can buy at lower prices and collect higher interest payments.

No matter what you decide, think several steps ahead and don’t get set on one way where you’re screwed if things don’t go as planned. Planning leads to options, options lead to adaptability.

1 https://www.investor.gov/introduction-investing/investing-basics/investment-products/bonds-or-fixed-income-products/bonds

2 U.S. Securities Exchange Commission (2009) Bankruptcy: What happens when public companies go bankrupt available at : https://www.sec.gov/reportspubs/investor-publications/investorpubsbankrupthtm.html (accessed: March 2021)

3 https://www.nytimes.com/2017/01/13/business/moodys-inflated-ratings-inquiry.html

4 Standard & Poor’s Rating Services. “Guide to Credit Rating Essentials: What are credit ratings and how do they work? https://www.spratings.com/documents/20184/760102/SPRS_Understanding-Ratings_GRE.pdf accessed

5 Council on Foreign Relations: “The Credit Rating Controversy”. https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/credit-rating-controversy accessed March 23, 2021

6 Moody’s Investor Services. “Sovereign default and recovery rates 1983-2019”. https://www.moodys.com/researchdocumentcontentpage.aspx?docid=PBC_1199619 accessed March 22, 2021

7 Robert W Baird & Co. Incorporated. Private Wealth Management Products & Services. “Sequence of return risk”. http://www.bairdfinancialadvisor.com/chris.trumble/mediahandler/media/118612/Sequence%20of%20Returns%20Risk.pdf Accessed April 16, 2021

8 Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (US), 20-Year Treasury Constant Maturity Rate [DGS20], Moody's Seasoned Aaa Corporate Bond Yield [AAA] retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/DGS20, April 11, 2021.

9 Moody’s Investor Services. “US Municipal Bonds defaults and recoveries, 1970-2019.” https://www.moodys.com/researchdocumentcontentpage.aspx?docid=PBM_1233833 accessed March 23, 2021

Dimensional Fund Advisors. Matrix Book 2019. Page 34. https://www.fplcapital.com/matrix-book-2019/

Get Our Latest Delivered To Your Inbox

You will receive 1-2 emails per month and you can unsubscribe at anytime