Inflation is when you pay fifteen dollars for a ten dollar haircut that you used to get for five dollars when you had hair.

- Sam Ewing Tweet

Home >> Protect >> What Is Inflation?

If you were born in the US after the stagflation period of 1973-1982, it is very unlikely that you’ve experienced “official” inflation north of 5% for any extended period of time. In fact, you’ve been dealing with CPI measured inflation in the 1-3% range for most of the past 30 years. There’s no wonder you have questions about what is inflation and what can be done to mitigate the harmful effects of inflation on your financial wealth.

This is a five-part series. In part one we’ll cover the basics of inflation such as what is inflation? and the different causes of inflation. In part two we’ll look at common measures of inflation. We’ll dissect the various problems and manipulations of the reported inflation measures in part three. Part four will cover the current level of inflation and address the transitory vs permanent debate. Finally, I will offer 30 actionable steps to protect yourself from the theft of inflation.

Summary

- Inflation is the reduction in purchasing power of your money.

- There are 3 primary causes of inflation

- Supply/Cost-push inflation: The demand for a good or service remains relatively constant while the supply decreases, or the cost of inputs go up.

- Demand-pull inflation: The supply of a good or service remains relatively constant while the demand increases.

- Monetary Inflation: Inflation as a result of changes in the quantity and/or velocity of money.

- The creation of new money can cause inflation as long as:

- The velocity does not fall at the same or higher rate than the money supply increases

- Real output does not rise at the same or higher rate than the money supply increases

- A combination of falling velocity and/or rising real output is not enough to fully offset the growth in the money supply

- The creation of new money can cause inflation as long as:

- Equation of Exchange

- P*Q = M*V

- The rate of change of inflation depends on the interplay between real output (Q), money supply (M), and the velocity of money (V).

- The theory has some serious drawbacks

- Our money supply measurements are not dynamic enough.

- The velocity of money is not a measurable variable. Instead, it is an algebraic calculation based on money supply and output.

- It is valuable in understanding the general relationships between those 3 components how they interact to affect the “general price level.”

- Equation of Exchange

What is inflation?

Most simply, inflation is the reduction in purchasing power of your money. There are 3 primary causes of inflation. In the cases of demand-pull and supply-push inflation, the supply of a good or service is not high enough to meet the demand.

On the other hand, monetary inflation reduces the value of your money due to a decrease in the scarcity of money rather than the supply of goods and services. It’s the same reason that water, one of the most important substances on earth, is so cheap; abundance.

Either way, you have to pay more for the same amount and quality of goods and services than before.

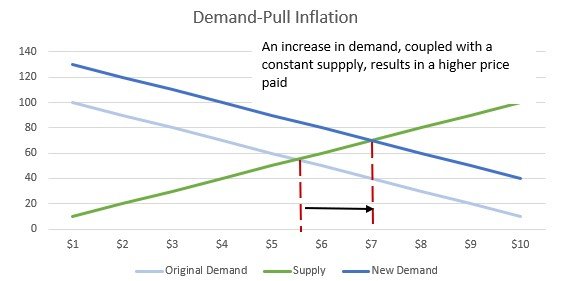

Demand-pull Inflation

Demand-pull inflation is the state in which the supply of a good or service remains relatively constant while the demand increases. It gets to a point where consumers conclude that so many people want an item that the best way to obtain it for themselves is to offer a higher price.

By far the most ridiculous example of demand-pull inflation in my lifetime was during Christmas of 1996. Tickle Me Elmo dolls were priced at $20-25 but were bid up to the $200-300 range because everyone had to have one for their child.

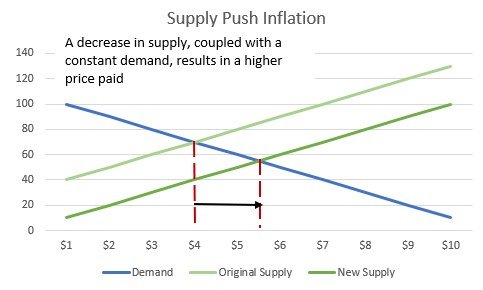

Supply-push (Cost-push) Inflation

There are two causes of supply side inflation. The first is due to supply chain bottlenecks/disruptions and the second is due to rising input costs.

Supply chain disruptions cause a decrease in supply while the demand of a good or service remains relatively constant. The supply decreases to a point where consumers conclude that an item is becoming scarce enough that the best way to obtain it for themselves is to offer a higher price. This is what happens when you hear the word shortage. There is not enough supply to meet the demand. It is usually temporary but can be permanent if the resources necessary for a product are permanently reduced.

The second cause of supply side inflation comes as a result of input costs increasing. Input costs are items such as labor costs, materials costs, energy etc.

In this case, there is no change in demand or supply. Rather, the cost of producing each unit increases due to rising input costs.

Input cost inflation can also be temporary or permanent. If there is a bottleneck in the supply chain of some material, it’s quite possible that the increase will be temporary. Once the bottleneck is cleared, the price of the material is likely to come down which brings the input costs back down. On the other hand, if a company or sector experiences higher wages, this cause of inflation is almost always permanent. Workers are unlikely to agree to a wage cut after receiving a raise.

Monetary Inflation

The best way to understand monetary inflation is through the Equation of Exchange.

Price level * Real Output = Money Supply * Velocity of Money

OR

P*Q = M*V

This theory states that nominal output (P*Q) must be equal to the amount of money in the economy (M) multiplied by the rate at which that money circulates (velocity – V).

Assuming the velocity of money is constant, If the amount of money in an economy increases by a larger percentage than the percentage increase in output, the price level must rise. This is the “too much money chasing too few goods” concept and is a very valuable theoretical tool that can help us understand the effects of money creation on prices. Let’s dive into each component:

An increase in output requires some offsetting combination of

- Higher Money supply

- Increased velocity of money

- Lower prices

If a combination of the money stock or velocity doesn’t increase enough to fully offset the increase in output, then prices must fall to balance the equation.

If the money supply and/or velocity increases more than the increase in output, then prices can actually rise.

A decrease in output requires the inverse of above.

An increase in the money supply requires some offsetting combination of

- Higher real output

- Higher prices

- Decreased velocity of money

If a combination of increasing output and/or falling velocity doesn’t fully offset the increase in money supply, then prices must rise to balance the equation.

If output rises and/or velocity falls more than the increase in money supply, then prices can actually fall.

A decrease in the money supply requires the inverse of above.

An increase in the velocity of money requires some offsetting combination of

- Higher real output

- Decreasing money supply

- Higher prices

If a combination of increasing output and/or falling money supply doesn’t fully offset the increase in velocity, then prices must rise to balance the equation.

If output rises and/or the money supply falls more than the increase in velocity, then prices can actually fall.

A decrease in the velocity requires the inverse of above.

Bad Assumptions Lead to Bad Conclusions

The right side (M*V) is where the Equation of Exchange breaks down. It makes two assumptions that have little evidence to support them.

We can accurately measure the money supply

The fact we’ve changed money supply measurements (M1, M2, M3 etc.) should be a clue that we aren’t entirely sure how to define money as it pertains to output.

Originally, we relied on M1 as the official measure of the money supply. However, “financial innovation posed problems for monetary measurement, as banks introduced new types of accounts that blurred the distinction between transaction deposits and other types of deposits. To accommodate these innovations, alternative definitions of money were created; By 1971, the Federal Reserve published data for five definitions of money.” 1

M1 was eventually ditched for a wider measure called M2 because the relationship between M1 and output broke down. The relationship between M2 and output has also broken down over the past 30 years leaving us in a similar situation.

One thing has become clear. Behavioral dynamics, financial innovation, and changing incentives imposed by regulations, often leads to changing forms of money. Since we haven’t been able to develop a measurement that dynamically adjusts to these changes, we haven’t been able to find a reliable relationship between our money supply measurements and output. As a result, we’ve relied on a calculation referred to as the velocity of money to capture this relationship.

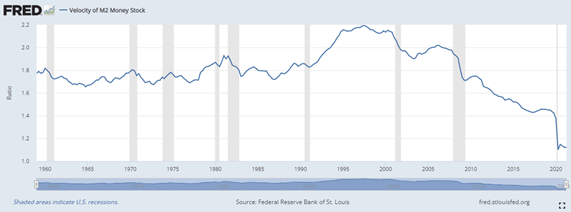

The velocity of money is measurable

The most common mistake while using the Equation of Exchange is to treat the velocity of money (V) as an independent variable that we can measure. In reality, nobody has come up with a way to actually measure the velocity of money. Instead, we algebraically derive it as V = (P*Q) / M.

In other words, the velocity is nothing more than a calculation. Once you understand this, it is no wonder that a spike in the money supply, without a corresponding spike in output, leads to a drop in the velocity of money.

Instead, velocity should be viewed as a black box that captures all the things that can affect the relationship between the money supply and output. It’s kind of like Total Factor Productivity that relates output to labor and capital in the production function.

Velocity is a catch all that includes things such as:

- Errors in our measurement of the money supply or output

- Financial innovations that change the forms of money

- Regulations that change consumer and business behavior

- Social changes that affect where and how wealth is stored or drawn upon

- True changes in the velocity of money

- Debt levels and it’s impact on consumer and business behavior

- The demand for money relative to the supply

- The wealth effect

These two assumptions lead to two conclusions which have been falsified over the past 20 years. First, an increase in the money supply without a corresponding increase in output will necessarily lead to an increase in inflation. It definitely can, but quantitative easing has proven that this is not always the case. Second, the unwillingness of consumers and business to spend is the reason that increases in money supply has not led to runaway inflation.

Even though the Equation of Exchange has it’s shortcomings, it’s still a valuable theory to grasp the high-level relationships between money and output.

As you now understand, there are several causes of inflation. Some have to do with supply constraints and input costs, and some have to do with consumers bidding up prices, while the flow and creation of money can also be a cause of inflation.

Now that you understand what is inflation and the primary causes of inflation, let’s move on to part 2: Common measures of inflation.

1 Monetary Aggregates and Monetary Policy at the Federal Reserve: A Historical Perspective by Chairman Ben S. Bernanke. https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/speech/bernanke20061110a.htm Accessed 11/26/2021

Get Our Latest Delivered To Your Inbox

You will receive 1-2 emails per month and you can unsubscribe at anytime